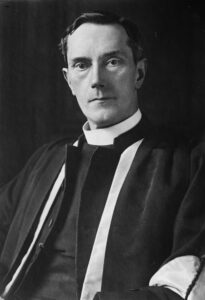

There is practically a cottage industry online of quote mining secondary sources to criticize the doctrines of the Incarnation and the Trinity. These quotations usually omit salient elements of those sources that would make them useless to the anti-Trinitarian polemicists. An example I recently discovered was the use of the early twentieth-century author William Ralph Inge to support the charge that the Nicene Creed represented a Platonist distortion of Christianity. Carlos Xavier, a Biblical Unitarian apologist, provides a good example of this usage:

There is practically a cottage industry online of quote mining secondary sources to criticize the doctrines of the Incarnation and the Trinity. These quotations usually omit salient elements of those sources that would make them useless to the anti-Trinitarian polemicists. An example I recently discovered was the use of the early twentieth-century author William Ralph Inge to support the charge that the Nicene Creed represented a Platonist distortion of Christianity. Carlos Xavier, a Biblical Unitarian apologist, provides a good example of this usage:

Thirdly, a strong argument can be made for the fact that the Nicene creed is in reality a Platonic creed. . . . William Inge, the famous professor of divinity, admitted that “Platonism is part of the vital structure of Christian theology.” Dr. Inge added that if Christians read Plotinus, who worked to reconcile Platonism with Scripture, “they would understand better the real continuity between the old culture and the new religion, and they might realize the utter impossibility of excising Platonism from Christianity without tearing Christianity to pieces.” So that early Christianity “from its very beginning was formed by a confluence of Jewish and Hellenic religious ideas.”[1]

To the casual reader—and especially to the anti-Trinitarian reader predisposed to view the matter in this way—these quotations from Inge might seem to confirm the opinion that Platonism corrupted Christianity. Indeed, Xavier asserts that, according to Inge, Plotinus “worked to reconcile Platonism with Scripture,” suggesting that Plotinus considered himself to be a Christian. However, Inge said no such thing. In fact, Plotinus was a pagan philosopher who did not engage Christianity in his writing.[2]

Xavier’s quotes come from Inge’s book on Plotinus, the third-century founder of Neoplatonism. Here is what Inge actually said (page breaks indicated in brackets; Xavier’s quotations underlined):

From the time when the new religion crossed over into Europe and broke the first mould into which it had flowed, that of apocalyptic Messianism, its affinity with Platonism was incontestable. St. Paul’s doctrines of Christ as the Power and the Wisdom of God; of the temporal things that are seen and the eternal things that are invisible; his theory of the resurrection, from which flesh and blood are excluded, since gross matter ‘cannot inherit the Kingdom of God’; and his psychology of body, soul, and spirit, in which, as in the Platonists, Soul holds the middle place, and Spirit is nearly identical with the Platonic Nous— all show that Christianity no sooner became a European religion than it discovered its natural affinity with Platonism. The remarkable verse in 2 Corinthians, ‘We all with unveiled face reflecting like mirrors the glory of the Lord, are transformed into the same image from glory to glory,’ is pure Neoplatonism. The Fourth Gospel develops this Pauline Platonism, and the Prologue to the Gospel expounds it in outline. One of the Pagan Platonists said that this Prologue ought to be written in letters of gold.

. . . [12] Platonism is part of the vital structure of Christian theology, with which no other philosophy, I venture to say, can work without friction.

. . . [13] We have thus to face a revolt against Platonism both in Protestant and Catholic theology. Those who sympathise with this anti-Hellenic movement are not likely to welcome my exhortations to read Plotinus. But if they would do so, they would understand better the real continuity between the old [14] culture and the new religion, and they might realise the utter impossibility of excising Platonism from Christianity without tearing Christianity to pieces. The Galilean Gospel, as it proceeded from the lips of Christ, was doubtless unaffected by Greek philosophy; it was essentially the consummation of the Jewish prophetic religion. But the Catholic Church from its very beginning was formed by a confluence of Jewish and Hellenic religious ideas, and it would not be wholly untrue to say that in religion as in other things Graecia capta ferum victorem cepit.[3]

According to Inge, while Jesus himself was not influenced by Greek philosophy, both Paul and John were. Now, I do not agree with Inge’s views on Platonism in Paul or John. My point is that neither does Xavier—at least, I presume that he does not agree with Inge. Xavier misrepresents Plotinus (as explained earlier) and quotes bits and pieces of text from Inge to make it sound as though Inge supports Xavier’s view that Christianity came under Greek philosophical influence sometime after the New Testament period. That is definitely not Inge’s position. When Inge says “from its very beginning,” he means from the earliest New Testament writings—specifically, those of the apostle Paul. If Platonism is bad (as Xavier but not Inge claims), and if Paul and John were Platonists (as Inge claims while Xavier hides Inge’s point), then the teachings of Paul and John were bad. Thus, Xavier has simply misrepresented Inge.

Inge’s interpretation of Paul and John is in important ways quite flawed. For example, Paul viewed resurrection as genuinely bringing back to life the dead body, though for Christ and those in Christ this included becoming immortal and incorruptible. The problem with the current body is not that it is “gross matter” but that it is mortal, weak, and corruptible (1 Cor. 15:42-54).[4] Platonists, by contrast, rejected resurrection outright. Nevertheless, there were elements in early Jewish and Christian teaching that found counterparts or similarities in Greek philosophy, including Platonism, and one can find such elements in the New Testament. The simplistic dichotomy between “Jewish” and “Hellenic” concepts doesn’t fit ancient Judaism or New Testament Christianity. For that very reason, blaming the doctrines of the Incarnation and the Trinity on Greek philosophy proceeds from the false assumption that everything in Greek philosophy is bad and goes downhill from there.

NOTES

[1] Carlos Xavier, “The Dark Legacy of the Nicene Creed,” TheHumanJesus.org, Sept. 9, 2022; YouTube, Dec. 20, 2022. Similarly, Troy Salinger, “What Scholars Say,” Let the Truth Come Out, n.d.; anon., “How Plato Influenced Our View of God,” One God Worship, n.d.; benadam 1974, “Logos Admits Pagan Christianity!” Simply Christian, Jan. 25, 2022. This or a similar quotation from Inge is also circulating on Facebook.

[2] On Plotinus, see the following accessible articles: Edward Moore, “Plotinus,” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, n.d.; Paul Kalligas, “Plotinus,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Sept. 25, 2024.

[3] William Ralph Inge, The Philosophy of Plotinus, The Gifford Lectures at St. Andrews, 1917–1918 (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1918), 1:11, 12, 13–14.

[4] See Kenneth D. Boa and Robert M. Bowman Jr., Sense and Nonsense about Heaven and Hell (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2007), 70–79, and the academic studies cited there. You can find information about the book here.