We saw in the first article in this series that the LDS Church accepts the same books in the Old Testament that are in the Jewish canon of Scripture and in the Protestant Old Testament. Yet they deny the inspiration of one of those books (Song of Solomon) without dropping it from their scriptures, while they fault the Old Testament for lacking other books. We will explore this criticism about missing books here.

We saw in the first article in this series that the LDS Church accepts the same books in the Old Testament that are in the Jewish canon of Scripture and in the Protestant Old Testament. Yet they deny the inspiration of one of those books (Song of Solomon) without dropping it from their scriptures, while they fault the Old Testament for lacking other books. We will explore this criticism about missing books here.

The Mormon Argument about “Lost Books”

The premise of the argument is that the Old Testament itself contains references to books not found in the Old Testament. The LDS Church’s own Bible Dictionary, in an entry on “Lost Books,” describes these books as “those documents that are mentioned in the Bible in such a way that it is evident they were considered authentic and valuable but that are not found in the Bible today. Sometimes called missing scripture, they consist of at least the following. . . .” The entry then lists eleven of these “lost books.”[1]

The statement that the books are “sometimes called missing scripture” is soon clarified to be the LDS Church’s own position. The entry thus goes on to assert that the Old Testament references to these books are “rather clear references to inspired writings other than our current Bible.” It further states that these references “attest to the fact that our present Bible does not contain all of the word of the Lord that He gave to His people in former times and remind us that the Bible, in its present form, is rather incomplete.”

The significance of this argument in the context of the LDS religion is that the supposedly missing scriptures of the Bible are precedent for the production of new scriptures, including other lost books, especially the Book of Mormon. As Kristian S. Heal and Zach Stevenson put it, “The canon had once been bigger, so why not again?”[2]

This argument has been part of Mormon apologetics going back to Joseph Smith himself, who commented on the “lost books” as early as 1833, just three years after publishing the Book of Mormon.[3] In 1842, Benjamin Winchester published a Synopsis of the Holy Scriptures that was a precursor to today’s LDS “Study Aids,” with a list of “books mentioned in the Bible that are not to be found among the sacred writings” that is very similar to the current entries on the topic.[4] The argument was repeated with virtually the same list of “missing scripture” by LDS apostle James Talmage in his popular books Articles of Faith[5] and Jesus the Christ.[6] The Encyclopedia of Mormonism cites some of the same references to support the claim that the Bible “testifies to its own incompleteness” because it “mentions sacred works that are no longer available.”[7] Likewise, LDS apologist Matthew Brown also claims, “The Bible itself provides clear evidence that it is not complete since it mentions scriptural texts that are now missing.”[8] Suffice it to say that this argument is standard fare in Mormon teaching.

What Would Count as “Lost Books of the Bible”?

Let’s be clear as to what the issue is here—and what it is not. First, everyone agrees that at least some of these books (more precisely, scrolls) are “lost” in the sense that they are not extant (i.e., no copies of them are available today). That is an entirely noncontroversial claim.

Continue reading →

Amazon’s ranking of book reviews may be a mystery to many readers. I know it was for me. Take, for example, its ranking of “top reviews” of the infamous book Pigs in the Parlor, which teaches that every Christian has at least one demon from which he or she needs to be “delivered.”

Amazon’s ranking of book reviews may be a mystery to many readers. I know it was for me. Take, for example, its ranking of “top reviews” of the infamous book Pigs in the Parlor, which teaches that every Christian has at least one demon from which he or she needs to be “delivered.” This article is the first in a projected series on Mormonism and the Old Testament. Throughout this year (2026), the LDS Church’s official curriculum Come, Follow Me takes members through the Old Testament.

This article is the first in a projected series on Mormonism and the Old Testament. Throughout this year (2026), the LDS Church’s official curriculum Come, Follow Me takes members through the Old Testament. In 2024, I began research on Alma 5:3–62, a speech that the Book of Mormon attributes to a first-century BC Israelite prophet in the Americas named Alma. This research investigates proposed evidence for and against the speech's antiquity. I’m pleased to announce a series of four new papers resulting from this research. Two of the papers respond to arguments for the ancient origin of the speech. The other two papers present evidence for its modern origin. You can find all four papers in the

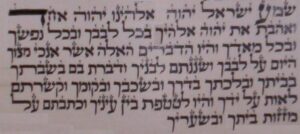

In 2024, I began research on Alma 5:3–62, a speech that the Book of Mormon attributes to a first-century BC Israelite prophet in the Americas named Alma. This research investigates proposed evidence for and against the speech's antiquity. I’m pleased to announce a series of four new papers resulting from this research. Two of the papers respond to arguments for the ancient origin of the speech. The other two papers present evidence for its modern origin. You can find all four papers in the  My paper, "From the Shema to the Homoousios: The Jewish Roots and New Testament Origins of the Nicene Creed," has now been uploaded to

My paper, "From the Shema to the Homoousios: The Jewish Roots and New Testament Origins of the Nicene Creed," has now been uploaded to  This is a follow-up to my previous post, “

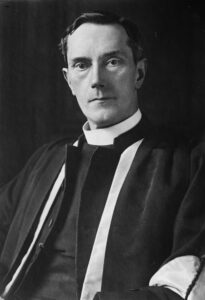

This is a follow-up to my previous post, “ There is practically a cottage industry online of quote mining secondary sources to criticize the doctrines of the Incarnation and the Trinity. These quotations usually omit salient elements of those sources that would make them useless to the anti-Trinitarian polemicists. An example I recently discovered was the use of the early twentieth-century author William Ralph Inge to support the charge that the Nicene Creed represented a Platonist distortion of Christianity. Carlos Xavier, a Biblical Unitarian apologist, provides a good example of this usage:

There is practically a cottage industry online of quote mining secondary sources to criticize the doctrines of the Incarnation and the Trinity. These quotations usually omit salient elements of those sources that would make them useless to the anti-Trinitarian polemicists. An example I recently discovered was the use of the early twentieth-century author William Ralph Inge to support the charge that the Nicene Creed represented a Platonist distortion of Christianity. Carlos Xavier, a Biblical Unitarian apologist, provides a good example of this usage: As I noted in my previous post on the 2025 Ligonier/Lifeway

As I noted in my previous post on the 2025 Ligonier/Lifeway

What do most members of evangelical churches in America believe? As I mentioned in my previous blog post, the Ligonier/Lifeway

What do most members of evangelical churches in America believe? As I mentioned in my previous blog post, the Ligonier/Lifeway