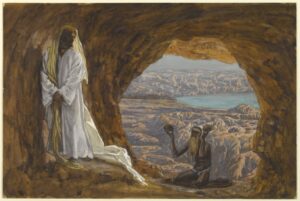

Jesus Tempted in the Wilderness, by James Tissot (ca. 1890)

In an article published on April 1, 2021, two Christian scholars argued that Jesus had “moments of doubt.” The Christianity Today article, by A. J. Swoboda of Bushnell University and Nijay K. Gupta of Northern Seminary, is entitled “Jesus Was the God-Man, Not the God-Superman.” Three days later, Robert Orlando, the filmmaker and founder of Nexus Media who has also written on biblical topics, had an opinion piece posted on the conservative website Townhall.com entitled “Was Jesus a Momentary Agnostic?” Orlando also argues that “Jesus was capable of doubt.” Many Christians will be surprised by the claim that Jesus experienced doubt. The issue is clearly worth considering.

Swoboda and Gupta begin as follows:

In many children’s Bibles, the Son of God swoops in like Superman to save the day. In these clearly mythological depictions of Christ, Jesus never fails to say and do the right thing.

This is a very worrisome beginning. Do Swoboda and Gupta think that on any occasion Jesus failed “to say and do the right thing”? Such a claim would go beyond the idea that Jesus doubted.

Swoboda and Gupta give no specific examples of such “edited stories” in “children’s Bibles,” making it difficult to assess their claim. As it stands, we have grounds to be skeptical that any “children’s Bible” gives “clearly mythological depictions of Christ,” unless they really mean that depicting Jesus as always saying and doing the right thing is mythological.

Of course, we agree that Jesus “breastfed as an infant,” “learned to walk,” “went through puberty,” and the like. That’s all noncontroversial. But then Swoboda and Gupta assert that “part of what he received from us in his humanness was our ability to doubt—and doubt he did.” This is the thesis of the article: that Jesus doubted. Did he?

I doubt it.

Did the Devil Tempt Jesus to Doubt He Was the Son of God?

The authors point out that the devil tempted Jesus with the words, “If you are the Son of God” (Matt. 4:3; see also Matt. 4:6; Luke 4:3, 9). They correctly observe that “the real human Jesus could be tempted—though he did not sin.” However, being tempted to doubt is not the same thing as doubting. Neither in the Temptation narratives in Matthew and Luke nor anywhere else in the Gospels is Jesus ever portrayed as doubting anything.

Moreover, the Temptation narratives do not support the claim that Jesus was even tempted to doubt. Swoboda and Gupta believe that in the Temptation narratives, “we learn that the real human Jesus comes face to face with doubts about his identity.” This interpretation is almost certainly mistaken. The “if” clauses of the two temptations in which those words appear do not express the sin to which Jesus was tempted. Rather, the sin that Jesus was tempted to commit was expressed in the “then” clauses:

“If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread” (Matt. 4:3; Luke 4:3).

“If you are the Son of God, throw yourself down…” (Matt. 4:6; Luke 4:9).[1]

Jesus was tempted to abuse his power or position as the Son of God by commanding stones to turn into bread or by throwing himself down from the pinnacle of the temple, both of which would have been self-serving actions inconsistent with his mission. The texts do not indicate that Jesus was even tempted to doubt that he was God’s Son, let alone that he did doubt that truth.

Some technical grammatical stuff here: The wording in Greek, using the particle εἰ (“if”) followed by a verb in the indicative mood (here, εἶ, “you are”), expresses what grammarians call a first-class condition. The “if” clause (the protasis) assumes something as true and then on that basis makes the claim or challenge in the “then” clause (the apododis). The “if” clause is not expressing doubt or calling on the hearer to doubt what that clause expresses.[2] This means that the devil was not tempting Jesus to doubt the truth of his identity as the Son of God.[3]

Thus, regarding the first temptation in Luke’s account, Joel Green astutely comments, “The devil does not deny that Jesus is God’s Son, but exploits this status by urging Jesus to use his power in his own way to serve his own ends; he thus reinterprets ‘Son of God’ to mean the opposite of faithful obedience and agency on God’s behalf.”[4] Similarly, R. T. France, in his comment on the first two temptations in Matthew’s account, states, “The following clauses do not cast doubt on this filial relationship, but explore its possible implications: what is the appropriate way for God’s Son to behave in relation to his Father? In what ways might he exploit this relationship to his own advantage?”[5]

In short, Jesus was tempted, not to doubt that he was the Son of God, but to abuse his power or status as the Son of God. Frankly, there is no basis in the accounts for the conclusion that Swoboda and Gupta draw: “Jesus passes the test, but his faith may have taken a heavy beating.”

Did Jesus Have Doubts in the Garden of Gethsemane?

Swoboda and Gupta, as well as Orlando, also find evidence of Jesus doubting in the account of Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane: “My Father, if it be possible, let this cup pass from me; nevertheless, not as I will, but as you will” (Matt. 26:39). Here is how Swoboda and Gupta present this prayer:

What does Jesus do? He starts getting cold feet: “If it is possible, may this cup be taken from me.” A moment later, of course, he shakes this off and confesses, “Yet not as I will, but as you will” (v. 39). But this is not faith replacing doubt; it is faith moving forward in spite of doubt.

This interpretation requires the authors to separate Jesus’ prayer into two prayers separated by “a moment” during which he “shakes off” his earlier doubt. None of the three accounts of Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane will sustain this reinterpretation (see also Mark 14:36; Luke 22:42). Of course, it is possible that all three Gospels are giving us an abbreviated account that omits such things as gaps of time between parts of Jesus’ prayer, but there is no basis for reading such gaps into the accounts. All three Gospels present Jesus expressing a single thought: He would like not to have to “drink” of the “cup,” but he accepts the Father’s will.

Orlando comments on Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane, “His humanity asks if there is any other way, but then accepts he might never know without a radical acceptance.” Here again, an idea is being read into the accounts that is simply not there. The Gospels do not present Jesus as not knowing whether his death on the cross for our sins was the Father’s will. Jesus had just told his disciples that he was giving his body and blood in death to inaugurate the new covenant, and that this would happen as God had already determined, through his betrayal by one of the disciples (Matt. 26:20-29; Mark 14:18-25; Luke 22:19-22).

In this instance, those who claim Jesus expressed doubt in Gethsemane are reading the Gospels in an overly flat—dare I say literal—way. Having pointed out the misunderstanding of the grammar in the accounts of the devil’s temptations of Jesus, I would now caution that the exegete should not live by grammar alone. One must understand the force of Jesus’ prayer in its context. Daniel Wallace rightly points out that in this case, as in other contexts, what is called speech-act theory (considering what a particular expression of speech is meant to do) is very helpful. Wallace comments:

Thus, Jesus’ plea in the Garden, “If it is possible, let this cup pass from me” (Matt 26:39), though formally a first-class condition, is, on a deeper level, an expression of agony. It is an implicit request that already knows it cannot be fulfilled.[6]

Notice that the point is not that Jesus sailed through the ordeal in Gethsemane with nary a care. No, he experienced genuine anguish, real “agony,” over what was coming—precisely because he knew what was coming. John Nolland explains:

It can hardly be that Jesus entertains serious doubts about what he has understood to be the Father’s will, but a serious gap has opened between what he has understood as his Father’s will and what in the reality of his human life he can perceive as desirable. Jesus asks ‘if it is possible’, but ultimately he comes to be reassured that it is not possible and that despite his own natural recoil from the prospect, his coming death on the cross represents the best possible thing that can happen given the situation that exists. Jesus would be very happy to be told, ‘It is not necessary’, but he expects to be told, ‘It is necessary’.[7]

Was Jesus Like the First Son in His Own Parable?

In their comments about Jesus’ time in Gethsemane, Swoboda and Gupta offer the following comment on a parable that Jesus had told a few days earlier:

In that moment, Jesus embodied the first character in the parable of the two sons (Matt. 21:28–31): When told by his father to do the work that needed to be done, he declined before changing his mind (v. 29). The second son said yes at first but then didn’t go through with it. Perhaps the question Jesus asked his disciples after telling that parable—“Which of the two did what his father wanted?” (v. 31)—came back to mind and gave him clarity in the garden.

There are two serious mistakes here.

First, Jesus was not talking to his disciples when he asked that question. He was talking to “the chief priests and the elders of the people” who had challenged Jesus’ authority (Matt. 21:23). After he asked them the question about which of the two sons in the parable did what their father wanted, and they answered that the first son did, Jesus told them:

“Truly, I say to you, the tax collectors and the prostitutes go into the kingdom of God before you. For John came to you in the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him, but the tax collectors and the prostitutes believed him. And even when you saw it, you did not afterward change your minds and believe him” (Matt. 21:31b-32).

Obviously, Jesus was not directing his parable to the disciples. This is not a minor mistake: the second son in his parable is obviously aimed at the religious leaders who professed to do God’s will but were not doing it. As for the first son, Jesus explicitly interpreted that character as representing “the tax collectors and the prostitutes” who lived in open sin but then repented when they believed the message of John the Baptist.[8]

This leads us to the second serious mistake in Swoboda and Gupta’s interpretation: there is certainly no basis for thinking that Jesus would have compared himself to the first son in his parable. The tax collectors and prostitutes, represented by the first son, had actually sinned before repenting when they believed the message that John preached. Jesus had not sinned. He had never “declined” to do his Father’s will, nor did he decline to do so in Gethsemane. He did not need to repent.

Did Jesus Doubt God the Father While Dying on the Cross?

The final supposed example of Jesus doubting comes in the famous cry of dereliction, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Matt. 27:46; Mark 15:34). Both Orlando and the two co-authors Swoboda and Gupta cite this cry as evidence of Jesus experiencing doubt. Swoboda and Gupta state that at that moment Jesus was “suffocating in doubt.” Orlando muddies the waters by emphasizing that Jesus also experienced fear, anxiety, and pain, all of which we may reasonably agree was true. However, it does not follow that Jesus also experienced doubt at that moment.

In Jesus’ cry from the cross, he was actually quoting the first line of Psalm 22.[9] As Christians commonly recognize, Psalm 22 is one of several psalms of David that were prophetic of the future Messiah, and it contains the most graphic picture of his suffering on the cross (Ps. 22:7-8, 14-18). Just as we might quote the first line of a beloved hymn and be thinking really of the whole song, Jesus was quoting the first line of Psalm 22 because the whole Psalm related to his situation. In the context of Psalm 22 as a whole, the psalmist is not saying that God had really abandoned or forsaken him. Nor is the psalmist expressing “doubts” about God’s goodness or concern for him. Rather, David (and Jesus after him) is giving vent to the feeling that God seemed to have forsaken him, although David (and, clearly enough, Jesus also) was confident that God had not really abandoned him at all.

My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

Why are you so far from saving me, from the words of my groaning?

O my God, I cry by day, but you do not answer,

and by night, but I find no rest.

Yet you are holy,

enthroned on the praises of Israel.

In you our fathers trusted;

they trusted, and you delivered them.

To you they cried and were rescued;

in you they trusted and were not put to shame….

But you, O Lord, do not be far off!

O you my help, come quickly to my aid!

Deliver my soul from the sword,

my precious life from the power of the dog!

Save me from the mouth of the lion!

You have rescued me from the horns of the wild oxen!

I will tell of your name to my brothers;

in the midst of the congregation I will praise you:

You who fear the Lord, praise him!

All you offspring of Jacob, glorify him,

and stand in awe of him, all you offspring of Israel!

For he has not despised or abhorred

the affliction of the afflicted,

and he has not hidden his face from him,

but has heard, when he cried to him. (Ps. 22:1-5, 19-24)

Here again, as in Jesus’ prayer in Gethsemane, one must ask what Jesus was doing with the words of the first line of Psalm 22 (as well as what David was doing with them originally). Jesus’ question was not expressing the belief that God had abandoned him, nor was he doubting that God the Father still loved him. As Wallace notes, the line from Psalm 22:1, “though formally a question, is really an expression of profound pain.”[10] Jesus expressed that pain using the opening words of that Psalm precisely because he fully expected the Father to prove himself faithful in the end.

Jesus’ Example and Our Doubt

Swoboda and Gupta seek to make a pastoral application of their conclusion that Jesus experienced real doubts. They argue, “Doubt (like temptation) is not a sin…. Doubt cannot be understood as sin.” On this basis, they conclude that the church should be welcoming to those with doubts. There is a laudable concern underlying their argument, but the problem is that a possibly helpful application is being presented on the basis of a faulty and quite unhelpful interpretation. They write:

There are clear passages that warn about the trajectory of doubt (Matt. 14:31; 21:21; Mark 11:23; James 1:5–8). But there are equally clear biblical texts that speak to how someone walking through doubt can (and should) be a welcome part of the Christian community (John 20:24–29, Matt. 28:17). In fact, the command in Jude to “be merciful to those who doubt” (v. 22) implies that the doubters are meant to be in our midst.

There is some unfortunate equivocation throughout the article concerning the meaning of the word doubt, and it becomes glaring at this point. Our English word doubt has a range of meanings from lack of certainty to mistrust and rejection.

In John 20:24-29, Jesus chastises Thomas not for “doubt” (despite being known as “doubting Thomas”) in the sense of some measure of uncertainty, but for having been unbelieving. Before seeing Jesus, Thomas had announced that unless he saw and touched Jesus for himself, “I will not believe” (οὐ μὴ πιστεύσω, John 20:25). Then, when Jesus appeared to him, he told Thomas, “Do not be unbelieving [ἄπιστος], but believing [πιστός]” (20:27b NASB). Surely Swoboda and Gupta do not mean to suggest that Jesus was unbelieving. As for Thomas, hypothetically speaking, had he continued not believing that Jesus had risen from the dead, he would not have remained part of the apostolic group and indeed would not have been “part of the Christian community” at all.

The meaning of the words “but some doubted” when Jesus appeared to the eleven (and probably others) in Galilee (Matt. 28:17b) is highly contested. The Greek word used here (ἐδίστασαν) is commonly and appropriately translated “doubted.” Without going into great detail, we may simply observe that in context some of the eleven, or some of the others with them, were uncertain either about the reality of Jesus’ resurrection or (as I think more likely) the propriety of worshiping Jesus (see 28:17a). Either way, the verb expresses an uncertainty or lack of sureness that stems from a too meager faith (as the parallel in Matthew 14:31, the only other place in the New Testament where the same verb is used, confirms). Again, the Bible never attributes lack of faith or weakness of faith to Christ, whether with this particular word or in any other way.

There is a vexed, complex textual issue in Jude 22-23 arising from the discovery of an early papyrus (P72) that reads differently there from the conventional text, along with various other forms of the text, and I do not want to make this article longer than necessary.[11] Evidently, Jude urged Christians either to “convince” those who doubted (or “disputed”) or to “have mercy” on those who doubted. The likely idea is that Christians are to point out the truth in a compassionate, patient way to those who are in the church but are unsure what to believe due to the problem of false teachers in the church.[12] This is a different situation than someone who persists in skepticism or who evinces a lack of confidence in God or in Christ.

Swoboda and Gupta conclude: “He became one of us not to shame us for our doubts but to teach us how to doubt well, to doubt faithfully. And so we are somehow saved too by his doubts.” Their pastoral concern to help less mature believers struggling to understand the faith is legitimate, but that goal cannot be furthered by arguing that Jesus doubted his identity, his mission, or God the Father’s love. The New Testament does not support the claim that Jesus doubted. We are saved by Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross as the sinless Lamb of God, not by Jesus overcoming personal doubts.

NOTES

[1] All biblical quotations are taken from the ESV except as noted (and when quoting the two articles under consideration).

[2] Daniel B. Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics: An Exegetical Syntax of the Greek New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1996), 690–94 (with a comment specifically on Matt. 4:3, 693).

[3] Darrell L. Bock, Luke: 1:1–9:50, vol. 1, BECNT (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1994), 372.

[4] Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 194.

[5] R. T. France, The Gospel of Matthew, NICNT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 127.

[6] Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics, 704.

[7] John Nolland, The Gospel of Matthew: A Commentary on the Greek Text, NIGTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2005), 1099–1100.

[8] This is the consensus interpretation of the passage reflected in exegetical commentaries. See, e.g., Donald A. Hagner, Matthew 14–28, WBC 33B (Dallas: Word, 1995), 614; Ben Witherington III, Matthew, Smyth & Helwys Bible Commentary (Macon, GA: Smyth & Helwys, 2006), 401; David L. Turner, Matthew, BECNT (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2008), 509.

[9] The material in this paragraph is repeated from Robert M. Bowman Jr., The Word-Faith Controversy: Understanding the Health and Wealth Gospel (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2001), 171–72.

[10] Wallace, Greek Grammar Beyond the Basics, 704 n. 47.

[11] See the overviews in Richard J. Bauckham, 2 Peter, Jude, WBC 50 (Dallas: Word, 1983), 108–111; Jerome H. Neyrey, 2 Peter, Jude: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AYB 37C (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008), 85–86, and the studies they cite.

[12] Peter H. Davids, The Letters of 2 Peter and Jude, Pillar NT Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2006), 101.